Knee-Deep Thinking: Why Staying Shallow Holds Us Back

Safe feels easy, but the real growth happens when we wade deeper.

There’s something comforting about a first idea. It arrives fast. It feels clever. It’s the first answer that pops into your head, so surely, it must be right. Many students (and, let’s be honest, many teachers) treat that first idea like it’s the golden ticket. They scribble it down, turn it in, and mentally check the assignment off their list. Done and done.

But if we’re aiming to build real thinkers, creators, and problem-solvers, we need to reframe the idea that speed equals brilliance. Because here’s the truth: the first idea is rarely the best one. Often, it’s just the warm-up.

Creativity (and real understanding) takes more than a single pass. The good stuff comes when students pause, reflect, and take the risk to go a little deeper. And as teachers, we can create that space for them. We can build the pause into our practice. And we can show them that letting go of the first idea doesn’t mean failure. It means growth.

First ideas are often the most obvious. They’re the ones floating on the surface of our brains, things we’ve heard before, seen before, or copied from a familiar structure. That’s not a bad thing. Familiarity is comforting. But it’s also limiting.

Take the classic example of a “Create a poster” assignment. Ask students to make one, and you’ll likely see rows of tri-folds, a few too many sparkly markers, and a lot of clip art from the same Google search. It’s not that students don’t care. It’s that no one asked them to go further.

If we stop the creative process at that first idea, we miss out on what could have been. A comic strip instead of a poster. A podcast. A satire piece. A timeline made from music lyrics. A video skit with props made out of classroom supplies. The second idea, or the third, might be the one that shows not just what they know, but how they think. That’s where the magic lives.

One of the simplest and most powerful things we can do as educators is to build in the question: “What else?”

After a brainstorm, ask for two more ideas. Or, even better, twenty more. After a draft, suggest one small change and see where it leads. After a group presentation plan, give them five minutes to challenge one of their assumptions. You’re not redoing their work, you’re refining their thinking.

Even something as small as:

These questions help students think divergently. They push beyond autopilot and into creativity. They encourage students to explore instead of rushing to submit.

If you’ve never used the SCAMPER technique with students, it’s a brilliant (and surprisingly simple) tool for pushing ideas further. (From the minds of Bob Eberle and Alex Osborn) Each letter in SCAMPER stands for a creative prompt that encourages alternate thinking:

Let’s say students are working on an invention project. They’ve designed a backpack with extra compartments. Great first idea. Now, use SCAMPER.

Suddenly, the thinking shifts. The project goes from a quick “done” to a deep dive into possibility. Students are learning flexibility, innovation, and the value of iteration.

Letting go of the first idea doesn’t mean students have to start from scratch every time. Revision is about layering, not scrapping.

In your classroom, create moments that invite second drafts without making them feel like punishments. Try:

This helps normalize reflection and improvement. It also removes the fear of getting it wrong the first time, because students know they’ll have the chance to grow.

One of the most powerful ways to help students see the value of iteration is to connect it to real-world examples.

Think of the books students love. Most went through dozens of drafts. Authors revise constantly.

Think of the apps on their phones. Those didn’t get built overnight. Teams brainstorm, test, fail, fix, repeat.

Think of movies, music, games. All polished through multiple rounds of revision. Creative professionals don’t get things perfect the first time. They expect, and value, the process of revision.

Share this with your students. Let them see that this is not about “extra work.” It’s about real work. The kind that matters.

Encouraging students to move past their first idea builds something deeper than just stronger assignments. It builds confidence. When students learn they can generate new ideas, rethink old ones, and create something better with time, they feel more capable. More resilient. Less afraid to start.

Perfectionism often shows up as “I have to get this right the first time.” But when you model and celebrate the process, you help students shake that idea. Instead, they learn that good work grows. And they begin to see themselves as learners, not just performers.

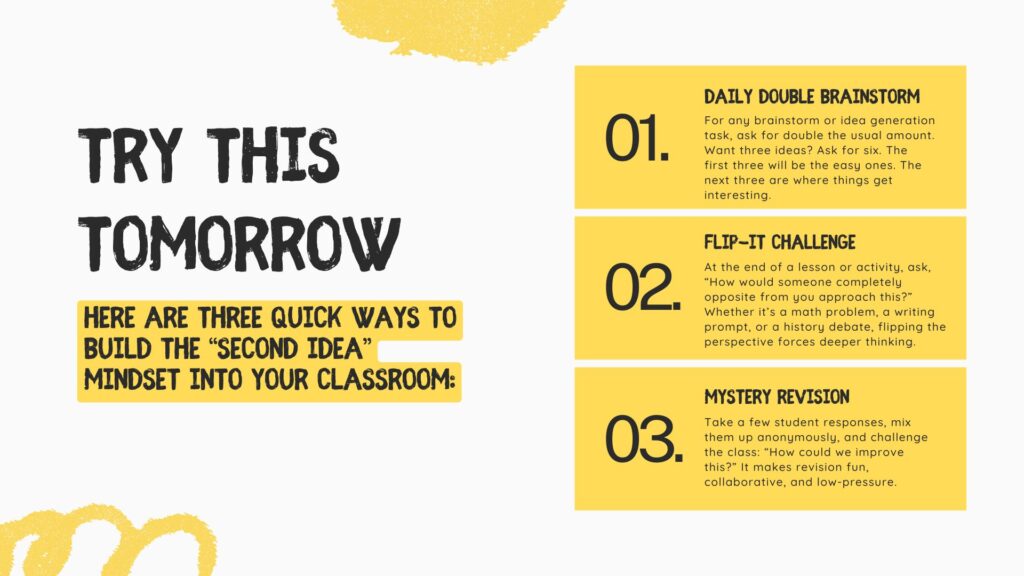

Looking for an easy place to start? Here are three quick ways to build the “second idea” mindset into your classroom:

1. Daily Double Brainstorm

For any brainstorm or idea generation task, ask for double the usual amount. Want three ideas? Ask for six. The first three will be the easy ones. The next three are where things get interesting.

2. Flip-It Challenge

At the end of a lesson or activity, ask, “How would someone completely opposite from you approach this?” Whether it’s a math problem, a writing prompt, or a history debate, flipping the perspective forces deeper thinking.

3. Mystery Revision

Take a few student responses, mix them up anonymously, and challenge the class: “How could we improve this?” It makes revision fun, collaborative, and low-pressure.

In a world that rewards fast answers, quick responses, and one-click submissions, helping students slow down is more important than ever. Learning isn’t about racing to the finish. It’s about understanding what’s possible when we take our time.

And creativity takes space. It takes curiosity. It takes the belief that the first idea might be fine, but the second, third, or even fifth might be brilliant.

The first idea is the spark. But we don’t build fires from sparks alone. We build them by feeding the flame.

So let’s teach students not just to finish, but to explore. Not just to answer, but to wonder. Not just to say “I’m done”, but to ask, “What could I try next?”

That’s where the real learning begins.

I’m Beth Slazak, the Vice-President of Curiosity 2 Create, a nonprofit organization offering professional development and coaching for educators and administrators.

We use the CREATE Method, an ESSA Level 4 backed method that reduces chronic absenteeism, improves student engagement, and increases student academic performance using our CREATE Method model. Schedule a call here to learn more about how Curiosity 2 Create and the CREATE Method can help you and your school today.

Share Post:

Safe feels easy, but the real growth happens when we wade deeper.

I can still picture it—walking through my northwest Chicago neighborhood with friends,

A lighthouse doesn’t shine just for decoration; it exists because lives depend